ONLINE INQUIRY

Human Epidermal Keratinocytes-fetal (HEK-f)

Cat.No.: CSC-7790W

Species: Human

Source: Epidermis; Skin

Cell Type: Keratinocyte

- Specification

- Background

- Scientific Data

- Q & A

- Customer Review

Human epidermal keratinocytes-fetal (HEK-f) are isolated from fetal skin and originate from the ectoderm. These cells differentiate through developmental stages into five layers: from the innermost to the outermost, they are the basal cell layer, spinous cell layer, granular layer, lucidum layer, and stratum corneum. As they mature through these structural layers, the morphology of fetal keratinocytes varies among different strata. Basal cells reside at the epidermis's lowest part, composed of a single layer of cuboidal or low columnar cells, and they continuously proliferate, moving towards the surface. The spinous cell layer is named for its spine-like projections between cells, while the granular layer comprises cytoplasm with numerous irregularly shaped keratohyalin granules of varying sizes. The lucidum layer generally appears only in thicker skin areas like palms and soles. The outermost stratum corneum contains cells whose cytoplasm is filled with keratin, having a thickened and robust membrane, with the gradual disappearance of the nucleus.

When stimulated by external factors, epidermal keratinocytes can detect pathogens through innate immune receptors, triggering antimicrobial responses and secreting various cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides. This process establishes the skin's physical barrier, constituting the first line of defense for the host. In the developmental phase, fetal epidermal keratinocytes exhibit relatively strong proliferative and differentiation potential to meet the growth and developmental needs of fetal skin. Consequently, fetal keratinocytes are pivotal in the construction of engineered skin tissues and are frequently utilized for studying congenital skin disorders and fetal developmental anomalies.

Fig. 1. Human fetal epidermal keratinocytes (Michalak-Micka K, Tenini C, et al., 2024).

Fig. 1. Human fetal epidermal keratinocytes (Michalak-Micka K, Tenini C, et al., 2024).

KLHL24 Degrades a Set of Keratins Expressed in Primary Foetal Epidermal Keratinocytes

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) with cardiomyopathy (EBS-KLHL24) is an EBS subtype caused by dominant mutations in the ubiquitin-ligase KLHL24 gene, leading to ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. While keratin 14 (K14) is known to be a target of KLHL24, it alone does not fully account for the pathology, as its levels remain unchanged in disease models. Logli's team aims to characterize the clonogenic and self-renewal properties of primary keratinocytes from EBS-KLHL24 patients and explored foetal keratins (K7, K8, K17, K18) as additional KLHL24 substrates.

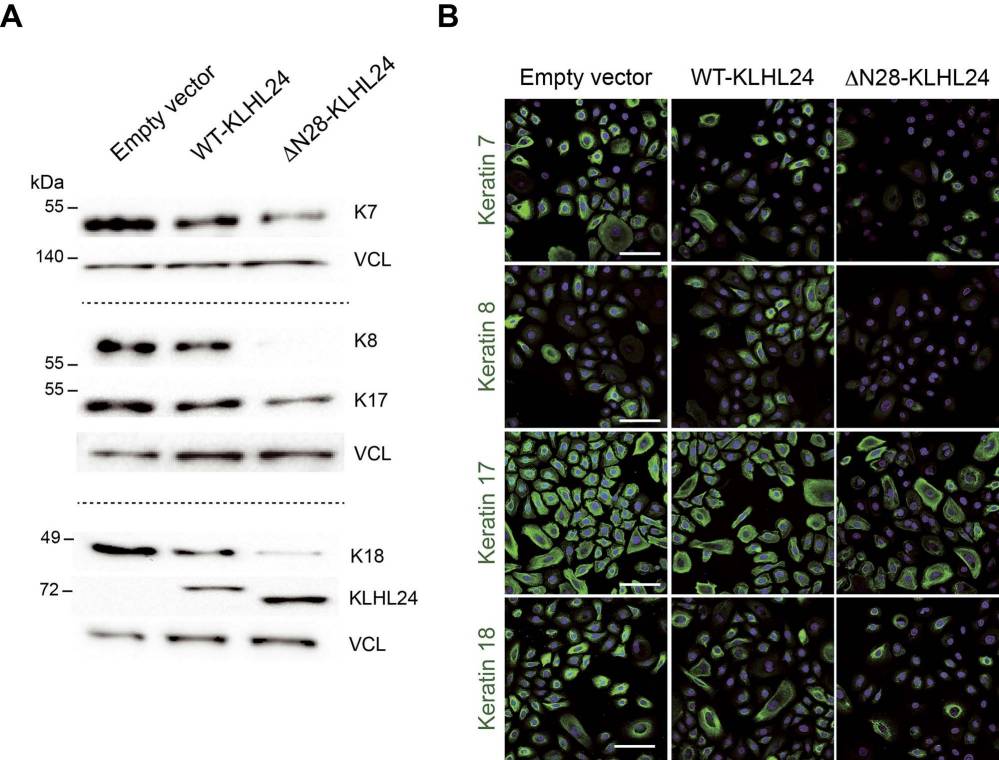

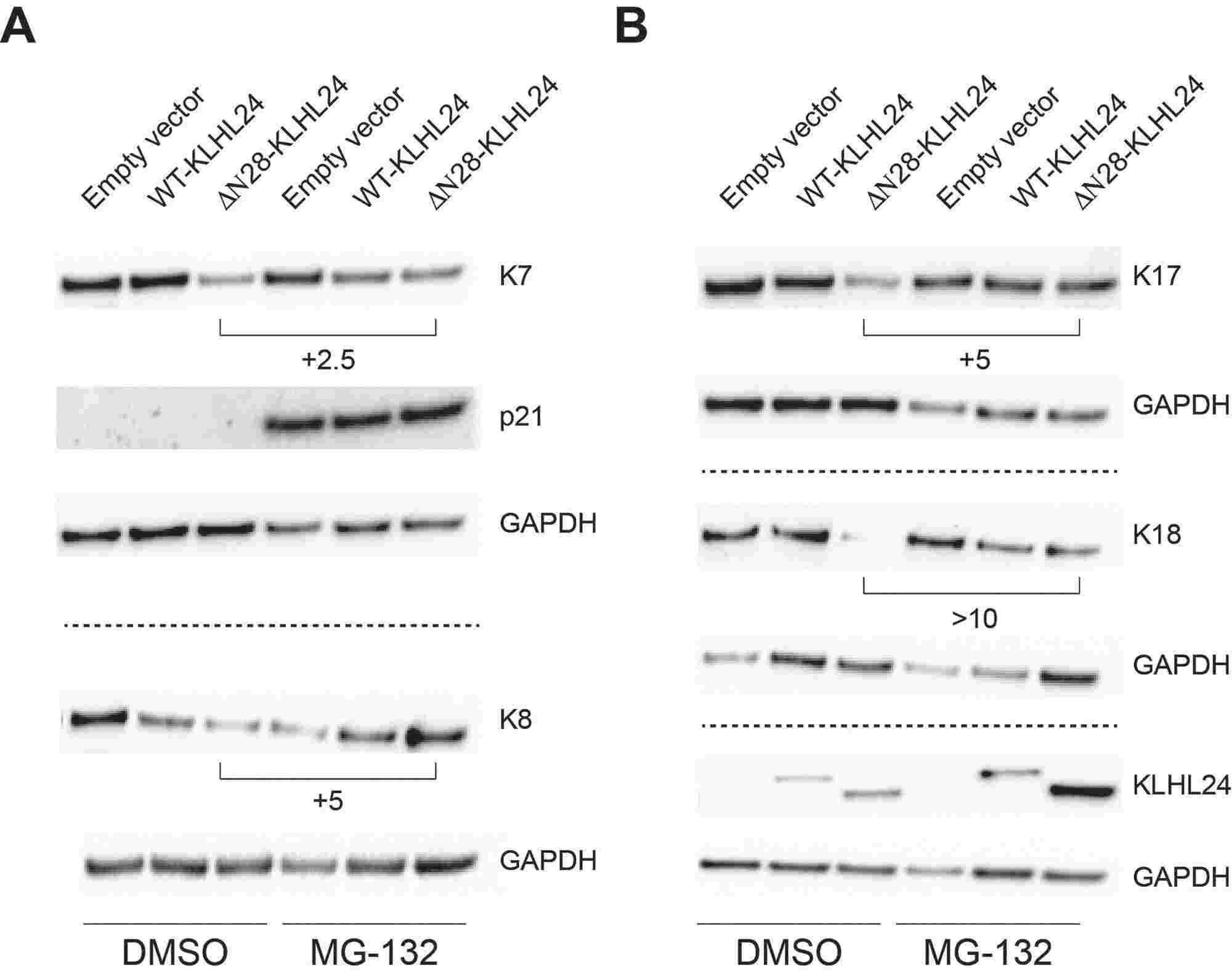

The results showed that keratinocytes from EBS-KLHL24 patients exhibited reduced colony formation efficiency and early senescence. They therefore hypothesized that one or more keratins expressed by keratinocytes during fetal epidermal development may represent additional KLHL24 targets. They investigated keratins K7, K8, K17, K18, and K19 in primary keratinocytes from fetal human epidermis (NHK-Fet), which were transduced with lentiviral particles carrying either wild-type KLHL24 (WT-KLHL24) or its truncated version (ΔN28-KLHL24). Immunoblotting revealed significant downregulation of K7, K8, K17, and K18 in cells expressing WT-KLHL24 or ΔN28-KLHL24 compared to controls (Fig. 1A), while K19 levels remained unchanged. The truncated ΔN28-KLHL24 displayed stronger degradation capabilities than WT-KLHL24. Confocal microscopy corroborated these findings, showing reduced staining of the aforementioned keratins in cells expressing the mutant KLHL24 form (Fig. 1B). Levels of K7, K8, K17, and K18 increased after treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Fig. 2). Collectively, these findings suggest that KLHL24 mediates the degradation of a set of keratins, including K7, K8, K17, and K18, in NHK-Fet via the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Fig. 1. Foetal keratin protein levels are strongly reduced in primary foetal keratinocytes transduced with the mutant KLHL24 form (Logli E, Marzuolo E, et al., 2022).

Fig. 1. Foetal keratin protein levels are strongly reduced in primary foetal keratinocytes transduced with the mutant KLHL24 form (Logli E, Marzuolo E, et al., 2022).

Fig. 2. Proteasome inhibition rescues foetal keratins from the degradation mediated by the mutant KLHL24 (Logli E, Marzuolo E, et al., 2022).

Fig. 2. Proteasome inhibition rescues foetal keratins from the degradation mediated by the mutant KLHL24 (Logli E, Marzuolo E, et al., 2022).

The Expression of CK6a in Cultured Keratinocytes In Vitro

Cytokeratins (CK) play a key role in wound healing. After skin damage, keratinocytes alter their cytokeratin composition, predominantly expressing type II CKs CK6a and CK6b along with their type I partners CK16 and CK17. To explore CK6a's potential as a wound healing marker, Michalak-Micka et al. analyzed its expression in keratinocytes from healthy skin, fetal and scar tissues, and skin substitutes.

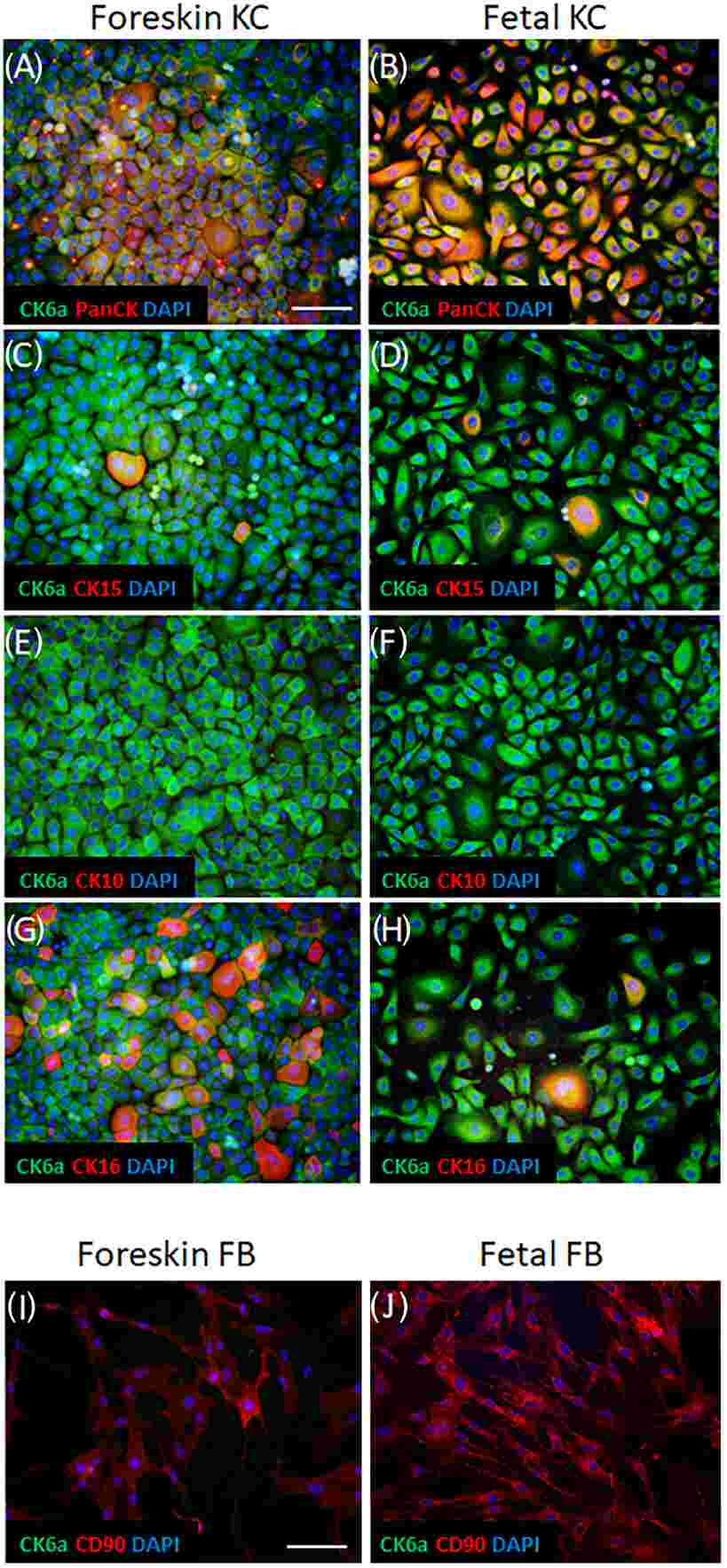

Initially, they explored protein expression in cultured keratinocytes by isolating primary human keratinocytes from fetal skin and foreskin samples and expanding them to passage 1 in vitro. Double immunofluorescence staining showed CK6a in all P1 cultured keratinocytes, aligning with PanCK expression, a keratinocyte marker (Fig. 3A and B). Cultured keratinocytes lacked the differentiation marker CK10 (Fig. 3E and F) and CK15 appeared in a few cells (Fig. 3C and D). More foreskin keratinocytes expressed CK16, a wound healing marker, compared to those from fetal skin (Fig. 3G and H). Fetal and foreskin fibroblasts, as negative controls, expressed only CD90, not CK6a (Fig. 3I and J).

Fig. 3. Expression pattern of CK6a in cultured keratinocytes in vitro (Michalak-Micka K, Tenini C, et al., 2024).

Fig. 3. Expression pattern of CK6a in cultured keratinocytes in vitro (Michalak-Micka K, Tenini C, et al., 2024).

Ask a Question

Write your own review