ONLINE INQUIRY

Human Skeletal Muscle Cells

Cat.No.: CSC-C1436

Species: Human

Source: Skeletal Muscle

Cell Type: Skeletal Muscle Cell

- Specification

- Background

- Scientific Data

- Q & A

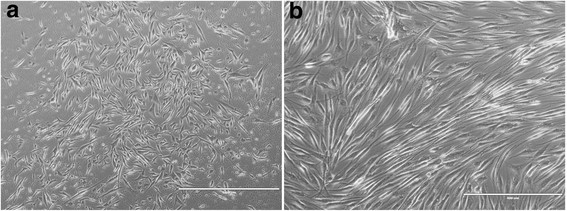

- Customer Review

The human skeletal muscle cell line is made from cells isolated and cultured from human skeletal muscle tissues, and provides an excellent tool for research into skeletal muscle biology and function. These cells have a long spindle shape with striations, and they don't branch. They are tightly packed and stick to bones, creating dense muscle fibers. Inside every muscle cell, a number of myofibrils lie along the cell's long side, with bright (I-band) and dark (A-band) patches. Such cells can grow into myotubes and multinucleated myocytes in vitro.

In their natural state, skeletal muscle cells are primarily responsible for motor functions. They contain abundant myofibrils, which are the fundamental units of muscle contraction. Upon receiving neural stimuli, these cells contract, resulting in movement. Additionally, they play a critical role in glucose uptake and metabolism, positioning themselves as pivotal tissues in energy metabolism. This cell line is widely used in the study of muscle disorders like muscle atrophy, dystrophy and metabolic syndromes. Simulating muscle development and regeneration in the lab allows scientists to study the development, regeneration and molecular signaling circuitry of muscle tissue. Additionally, these cell lines are critical for developing new drugs, cell therapies and gene editing systems.

Fig. 1. Low-resolution phase contrast of primary cultured human skeletal muscle cells and mature myotubes (Mattyasovszky S, Langendorf E, et al., 2018).

Fig. 1. Low-resolution phase contrast of primary cultured human skeletal muscle cells and mature myotubes (Mattyasovszky S, Langendorf E, et al., 2018).

L-Anserine Increases Muscle Differentiation and Muscle Contractility in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells

Skeletal muscle is vital for movement and metabolism, with declines from aging leading to conditions like sarcopenia. L-anserine, an imidazole peptide found in birds and fish, has various physiological benefits, may influence muscle function. But its effect on muscle differentiation and contractility is unknown. Therefore, Nagai et al. aims to explore L-anserine's impacts on these aspects in human skeletal muscle cells.

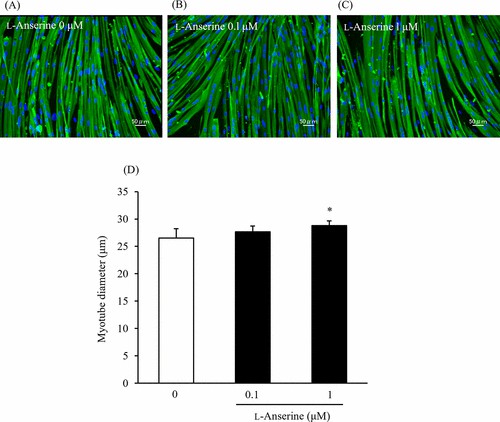

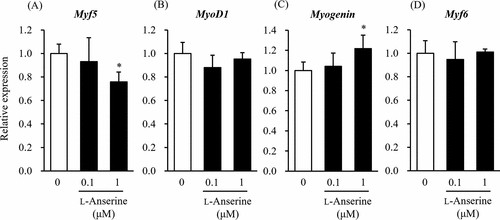

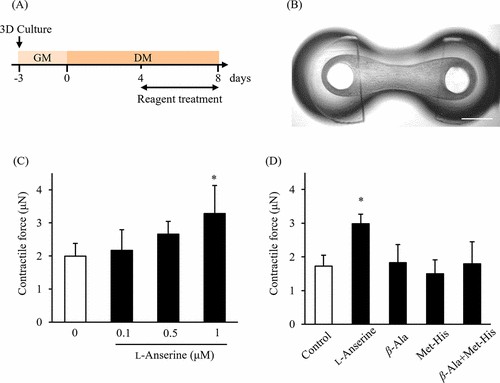

First, they examined the effects of L-anserine on the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells in two-dimensional (2D) culture by analyzing the myotube widths and gene expression levels. Figure 1 illustrates immunofluorescence staining results for Myh (Fig. 1A–C) and myotube diameters (Fig. 1D). ANOVA with Dunnett's test revealed a significant increase at 1 μM L-anserine compared to 0 μM. Muscle regulatory factors (MRFs) are crucial for myoblast differentiation, serving as markers of myogenic differentiation. Given that L-anserine increased myotube diameter (Fig. 1), they assessed MRFs gene expression (Fig. 2). At 1 μM L-anserine, Myf5 expression decreased significantly, while Myogenin increased (Fig. 2A and C), without affecting MyoD1 or Myf6 (Fig. 2B and D). As L-anserine enhances muscle differentiation and sarcomere protein gene expression. They tested its effect on engineered muscle tissues' contractile force (Fig. 3A) using a microdevice (Fig. 3B). Tissues treated with 1 μM L-anserine showed increased force after 96 hours (Fig. 3C). β-Alanine and 1-methyl-L-histidine, L-anserine components, showed no similar effects when tested individually or together (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 1. Effect of L-anserine on the myotube diameter (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Fig. 1. Effect of L-anserine on the myotube diameter (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Fig. 2. Effect of L-anserine on the mRNA expression levels of myogenic differentiation marker genes (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Fig. 2. Effect of L-anserine on the mRNA expression levels of myogenic differentiation marker genes (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Fig. 3. Effect of L-anserine on the contractile force in engineered human skeletal muscle tissues (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Fig. 3. Effect of L-anserine on the contractile force in engineered human skeletal muscle tissues (Nagai A, Ida M, et al., 2023).

Exposure to Radial Extracorporeal Shock Waves Modulates Viability and Gene Expression of Human Skeletal Muscle Cells: A Controlled In Vitro Study

Muscle injuries are prevalent in athletes, comprising over 30% of sports injuries. Current treatments for structural muscle injuries are limited, with inconclusive management strategies and inconsistent results from existing therapies. Mattyasovszky et al. exposed human skeletal muscle cells to radial shock waves in vitro to assess cell viability and gene expression, exploring the biological effects of radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT) on human skeletal muscle cells, proposing its potential as a non-invasive therapy to enhance recovery from sports-related muscle injuries.

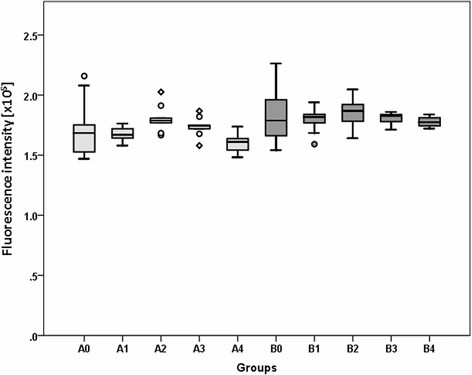

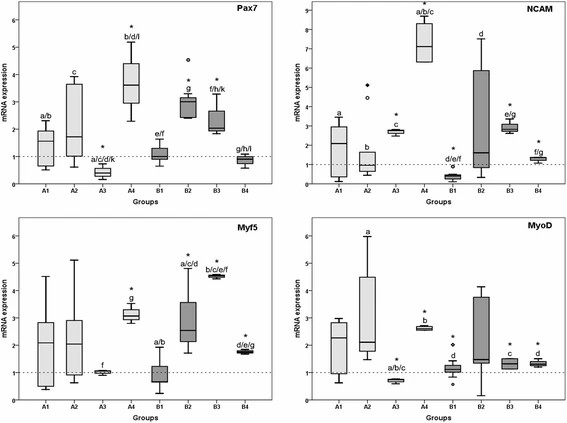

Exposure to rESWs affects human primary skeletal muscle cells' viability. Medium shock wave strength (2-3 bar; 0.09-0.14 mJ/mm2) offers the best cell viability, while higher applications decrease viability (Fig. 4). Although notable, differences aren't statistically significant. rESW impacts muscle-specific gene expression dose-dependently (Fig. 5). After one exposure, Pax7 increases significantly in the high AP and FD group (A4) but decreases in lower AP/FD groups. Double exposure at medium AP and FD (B2, B3) greatly affects cells. Comparing single to double exposure, Pax7 up-regulates in A3 and B3 (3 bar, 0.14 mJ/mm2) and down-regulates in A4 and B4 (4 bar, 0.19 mJ/mm2). MyoD's expression pattern mirrors Pax7's. For NCAM, there's significant up-regulation in groups A3, B3, and single exposure in A4 (3 bar, 0.14 mJ/mm2; 4 bar, 0.19 mJ/mm2). Highest EFD in double exposure significantly down-regulates compared to single. Myf5 up-regulates significantly after single exposure at highest EFD (A4, 4 bar, 0.19 mJ/mm2) and double exposure in B2-B4. Double exposure at second-highest EDF (3 bar, 0.14 mJ/mm2) peaks Myf5 expression, but highest EFD results in a down-regulation against single exposure, and B3. The above results show that shock wave exposure at low energy enhanced cell viability, while medium energy increased gene expression of key muscle markers. High energy exposure led to a down-regulation in gene expression after repeated exposure. This indicates potential modulation of muscle cell function by rESWT.

Fig. 4. Results of alamar blue assay to determine cell viability (Mattyasovszky SG, Langendorf EK, et al., 2018).

Fig. 4. Results of alamar blue assay to determine cell viability (Mattyasovszky SG, Langendorf EK, et al., 2018).

Fig. 5. Results of qRT-PCR analysis (Mattyasovszky SG, Langendorf EK, et al., 2018).

Fig. 5. Results of qRT-PCR analysis (Mattyasovszky SG, Langendorf EK, et al., 2018).

Ask a Question

Write your own review