ONLINE INQUIRY

Human Oral Keratinocytes (HOK)

Cat.No.: CSC-7745W

Species: Human

Source: Oral Cavity

Cell Type: Keratinocyte

- Specification

- Background

- Scientific Data

- Publications

- Q & A

- Customer Review

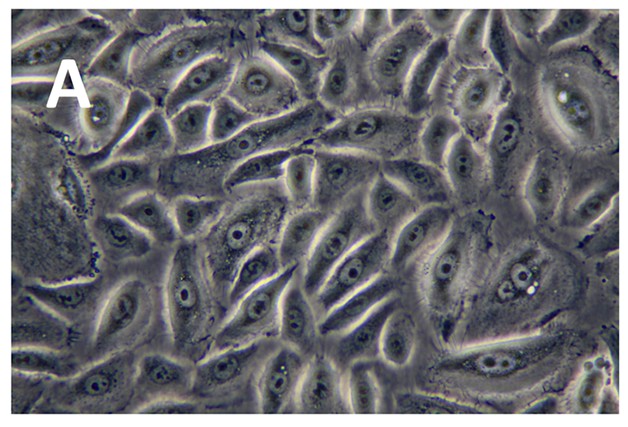

Human Oral Keratinocytes (HOK) originate from human oral mucosal tissues specifically from the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and tongue areas. Located in the basal layer of oral mucosa these cells divide and differentiate to create new epithelial cells which replace aged or damaged ones. Basal layer cells move toward the surface through migration until they develop into keratinized or non-keratinized epithelial layers. HOK exhibit typical epithelial morphology, adhering to surfaces and growing into multi-layered structures, demonstrating excellent stratification properties. In vitro, HOK can form multi-layered keratinized epithelial models that mimic the natural structure of human oral mucosa.

The barrier function of the oral mucosa depends crucially on the activity of HOK. These cells activate immune responses and repair tissues through the secretion of multiple cytokines including IL-1α, IL-6, and VEGF. Additionally, HOK have the ability to respond to external stimuli including hypoxic conditions and show changes in their undifferentiated phenotype. During oral disease studies researchers utilize HOK to understand the development of oral cancer and oral ulcers and gingivitis while also assessing drug and oral care product safety and effectiveness. Tissue engineering uses these cells to develop oral mucosal tissue models which help researchers investigate tissue regeneration and repair processes. Furthermore, HOK are employed to assess the toxic effects of chemicals and drugs on oral mucosa.

Fig. 1. Photomicrographs of HOK (light microscope with 400x magnification) (Islam R, Jackson C, et al., 2015).

Fig. 1. Photomicrographs of HOK (light microscope with 400x magnification) (Islam R, Jackson C, et al., 2015).

HOKs Challenged by Streptococcus sanguinis and Porphyromonas gingivalis Differentially Affect the Chemotactic Activity of THP-1 Monocytes

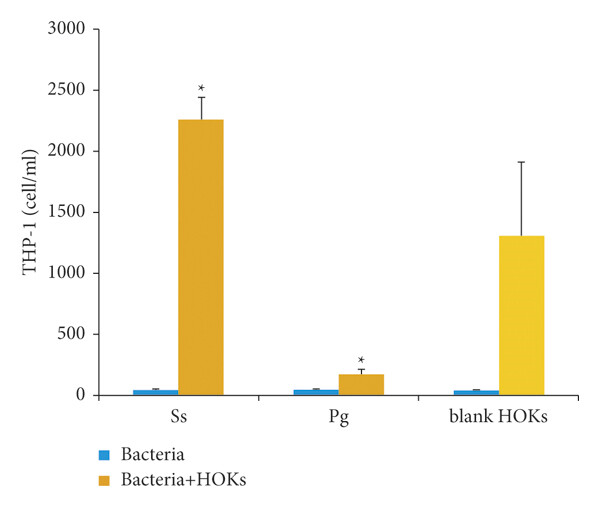

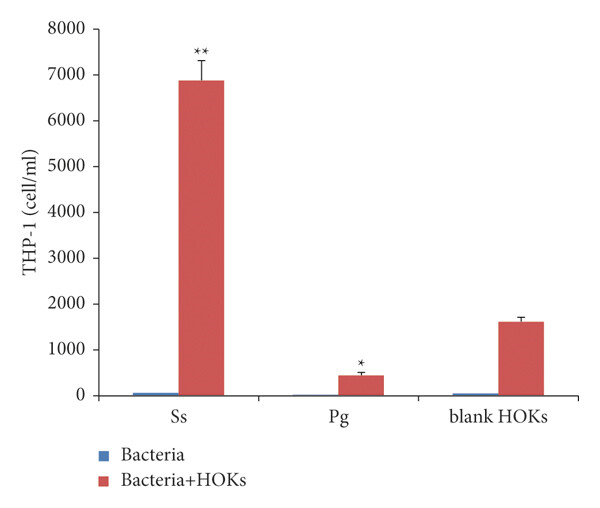

The transition from symbiotic microbe-host relationships to dysbiosis starts periodontal diseases which then lead to tissue destruction through a disrupted host response. The study by Li's team assessed how human oral keratinocytes (HOKs) exposed to either periodontal commensal bacteria or pathogens differentially impacted THP-1 monocyte chemotaxis.

Using a transwell migration assay, HOKs were challenged with S. sanguinis or P. gingivalis, and the mixed cultures were analyzed for THP-1 monocyte migration over 2 and 18 hours. Figure 1 demonstrates that the count of stained THP-1 cells in the lower compartment varied significantly between different groups. The control group featuring HOKs alone managed to attract a substantial number of THP-1 cells. THP-1 cell attraction by HOKs increased after S. sanguinis challenge but reduced following P. gingivalis challenge compared to control. The THP-1 cell count in the S. sanguinis-HOKs group exceeded the count in the P. gingivalis-HOKs group by more than tenfold which indicates a significant difference. Importantly, neither S. sanguinis nor P. gingivalis alone effectively attracted THP-1 cells compared to the blank control. After 18 hours of interaction, a similar pattern persisted among all groups (Fig. 2), with the S. sanguinis-HOKs group continuing to show markedly greater attraction, while the P. gingivalis-HOKs group attracted significantly fewer THP-1 cells, about 15 times lower than the S. sanguinis group.

Fig. 1. Chemotactic Effect on THP-1 Cells at 2 h (Li H, Seneviratne C J, et al., 2022).

Fig. 1. Chemotactic Effect on THP-1 Cells at 2 h (Li H, Seneviratne C J, et al., 2022).

Fig. 2. Chemotactic Effect on THP-1 cells at 18 h (Li H, Seneviratne C J, et al., 2022).

Fig. 2. Chemotactic Effect on THP-1 cells at 18 h (Li H, Seneviratne C J, et al., 2022).

Quercetin Attenuates LPS-Induced Human Oral Keratinocytes Injury

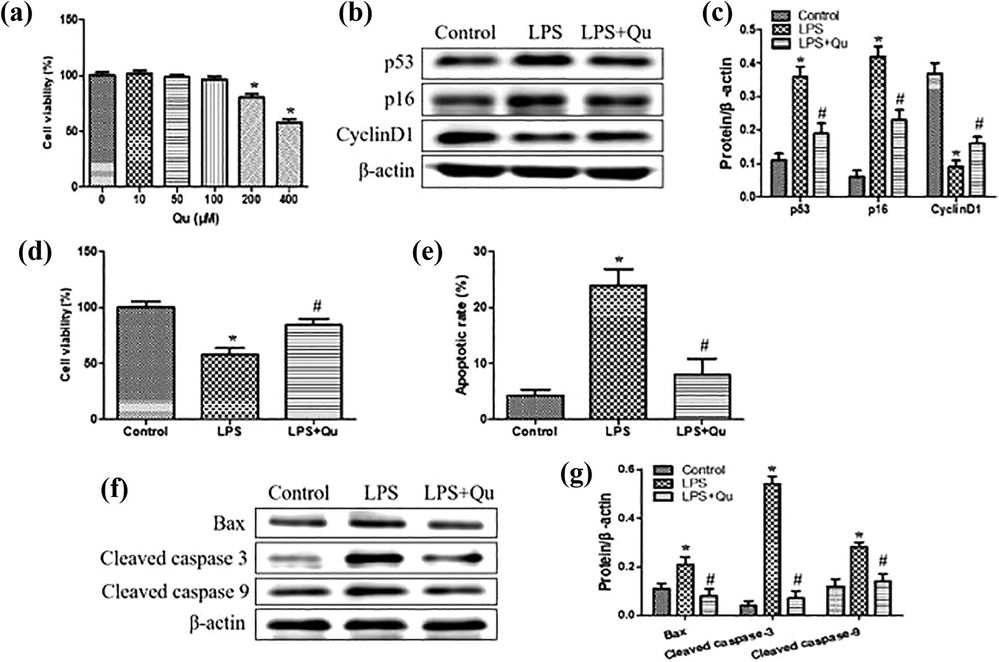

Quercetin produces anti-inflammatory effects but it remains uncertain whether these benefits apply to patients with oral lichen planus (OLP) because this common chronic mucocutaneous disease involves immune-mediated disease processes. Wang et al. developed a cell-based OLP model where HOKs were exposed to LPS to investigate the treatment potential of quercetin by examining downstream miRNAs and associated signaling pathways.

They first studied quercetin's effects on healthy human oral keratinocytes (HOKs) by exposing cell cultures to different quercetin concentrations to measure their viability. Cell viability remained stable when exposed to concentrations up to 100 μM but showed significant decline when concentrations reached between 200 and 400 μM (Fig. 3a). All following experiments utilized a quercetin maximum dose of 100 μM. Subsequent experiments treated HOKs with 100 ng/mL LPS while testing the presence or absence of 100 μM quercetin. LPS altered the levels of p53, p61, and cyclin D1 (Fig. 3b and c); quercetin effectively restored cell viability reduced by LPS (Fig. 3d); and LPS heightened apoptosis rates (Fig. 3e); while also changing Bax and cleaved caspases 3 and 9 levels (Fig. 3f and g). The findings demonstrate that quercetin can successfully reduce injury in HOK cells caused by LPS.

Fig. 3. Qu attenuates LPS-induced HOK injury (Wang F, Ke Y, et al., 2020).

Fig. 3. Qu attenuates LPS-induced HOK injury (Wang F, Ke Y, et al., 2020).

Human Oral Keratinocytes (HOK) are primary cells, but we do also have Immortalized Human Oral Keratinocytes in stock. They are both isolated from human gingiva tissues.

Ask a Question

Write your own review