ONLINE INQUIRY

Mouse Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells

Cat.No.: CSC-C1176Z

Species: Mouse

Source: Retina; Eye

Cell Type: Epithelial Cell

- Specification

- Background

- Scientific Data

- Q & A

- Customer Review

Mouse retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells develop from the retinal tissue found in mice. The retina serves as the innermost wall of the eyeball and contains both the pigment epithelial layer and the sensory layer. The retinal pigment epithelial cells occupy the retina's outermost layer where they maintain direct contact with the choroid. They play a crucial role in retinal development and function, including regulating retinal development, absorbing excess light to reduce photo-oxidative stress, secreting angiogenic factors such as VEGF, participating in immune responses, transporting metabolites, and phagocytosing the outer segments of rod and cone photoreceptors. RPE cells demonstrate either cuboidal or hexagonal shapes and contain large amounts of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria together with many microvilli which expand the cell surface area to boost absorption and metabolic activities.

Multiple eye diseases including retinitis pigmentosa and diabetic retinopathy display RPE cell degeneration and dysfunction together with macular degeneration. Mouse RPE cells are essential research models for human eye diseases because they share high genetic similarity with humans. Furthermore, the methods for isolating and culturing RPE cells continue to evolve to improve their representation of natural biological functions.

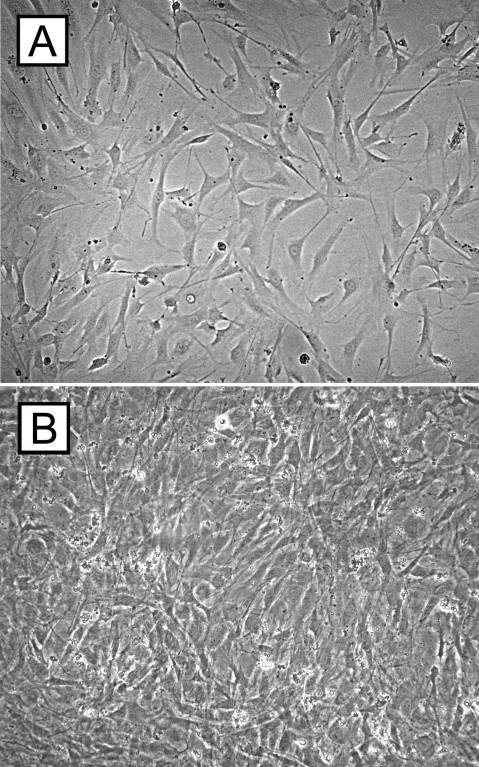

Fig. 1. Cell culture experiments of retinal pigment epithelium cells. The micrographs demonstrate C57BL/6 RPE cells after 3 (A) and 7 (B) days of cell culture (Schmack I, Berglin L, et al., 2009).

Fig. 1. Cell culture experiments of retinal pigment epithelium cells. The micrographs demonstrate C57BL/6 RPE cells after 3 (A) and 7 (B) days of cell culture (Schmack I, Berglin L, et al., 2009).

CRISPR-Mediated Prom1-KO Impairs Autophagy in mRPE Cells

Prominin-1 (Prom1) mutations are known to cause macular dystrophies and photoreceptor disk morphogenesis abnormalities. While Prom1 functions in human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) autophagy regulation, its role in mouse RPE is not well-documented. Bhattacharya et al. investigated whether Prom1 is essential for autophagy and phagocytosis in mouse RPE cells and to understand how its loss leads to RPE dysfunction and photoreceptor degeneration.

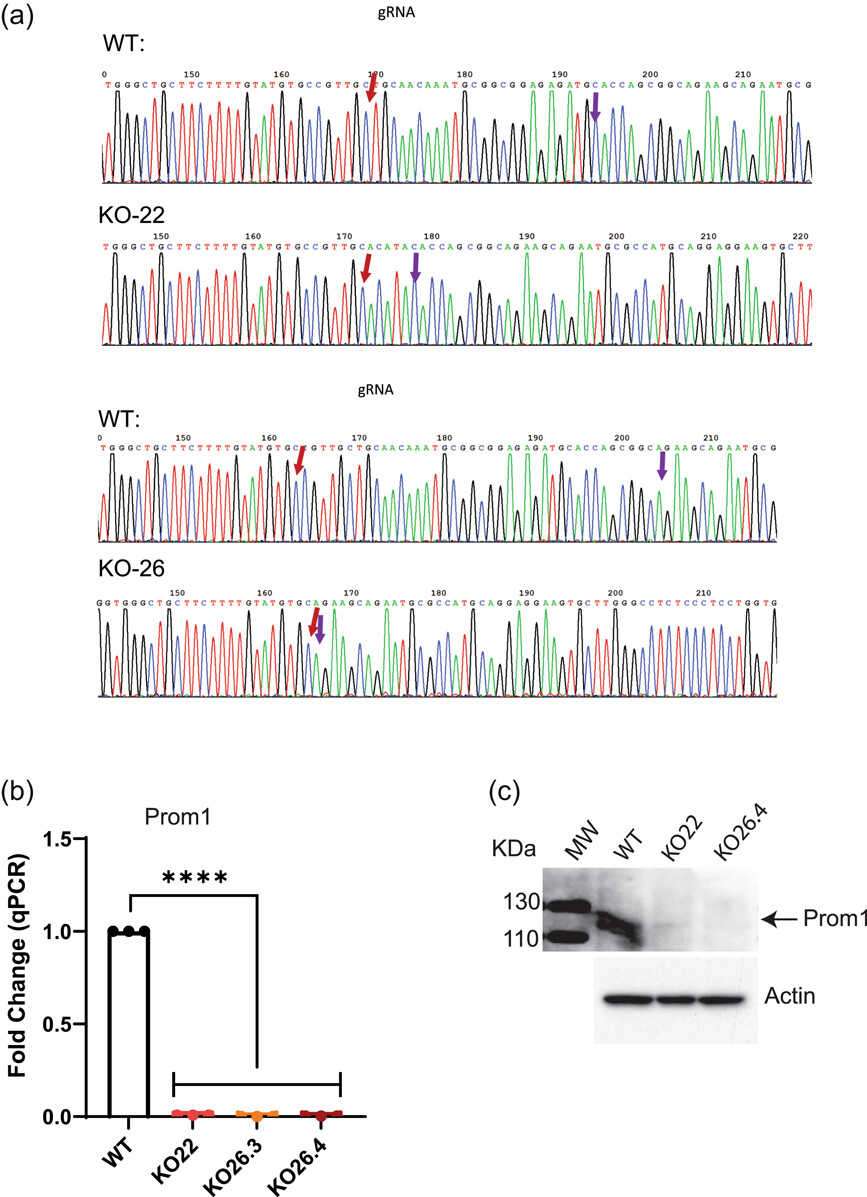

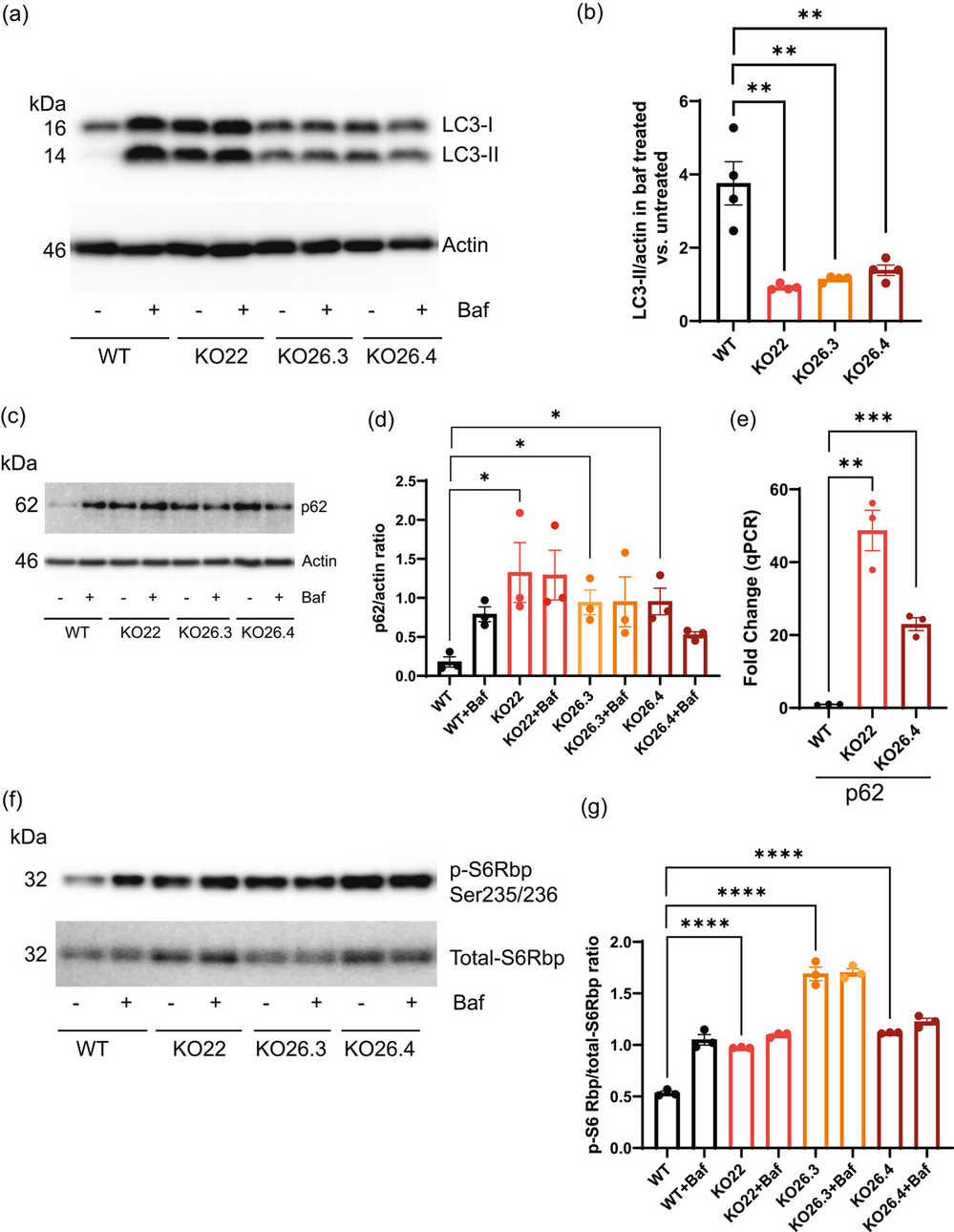

To explore Prom1's role in mRPE cells, they utilized CRISPR/Cas9 to delete Prom1. Sequence analysis revealed multiple base pair deletions in cells treated with Prom1 gRNA (Fig. 1a). Genomic sequencing confirmed unique deletions in KO22, KO26.3, and KO26.4 cells, used for the experiments (Fig. 1a). Real-time PCR and Western blot analysis confirmed the absence of Prom1 mRNA and protein, respectively (Fig. 1b and c). To test Prom1's involvement in autophagy, WT and Prom1-KO cells were treated with Baf to inhibit vacuolar-type ATPase, affecting LC3-II levels. WT cells showed low basal LC3-II, which increased with Baf, indicating autophagy flux inhibition. Prom1-KO cells had high basal LC3-II levels unaffected by Baf, highlighting reduced LC3-II turnover (Fig. 2a and b). p62 levels, an inverse marker for autophagy flux, were higher in Prom1-KO cells, indicating impaired autophagy. Baf did not affect p62 in Prom1-KO cells, suggesting reduced autophagosome turnover (Fig. 2c and d). Increased p62 transcription in Prom1-KO cells was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 2e), showing Prom1's inhibitory role on p62 transcription in mRPE.

Fig. 1. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Prom1 gene editing in mouse RPE cells (Bhattacharya S, Yin J, et al., 2023).

Fig. 1. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Prom1 gene editing in mouse RPE cells (Bhattacharya S, Yin J, et al., 2023).

Fig. 2. Prom1 deletion inhibits autophagy through p62 and mTORC1 signaling pathways in mRPE cells (Bhattacharya S, Yin J, et al., 2023).

Fig. 2. Prom1 deletion inhibits autophagy through p62 and mTORC1 signaling pathways in mRPE cells (Bhattacharya S, Yin J, et al., 2023).

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) is Essential to NAD+ and Down-stream SIRT1 Expression in RPE

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) supports retinal health and function by delivering nutrients and eliminating waste between photoreceptors and the choroidal blood supply. Aging and associated RPE dysfunction, such as decreased NAD+ levels, are critical factors in degenerative retinal diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which causes blindness in the elderly.

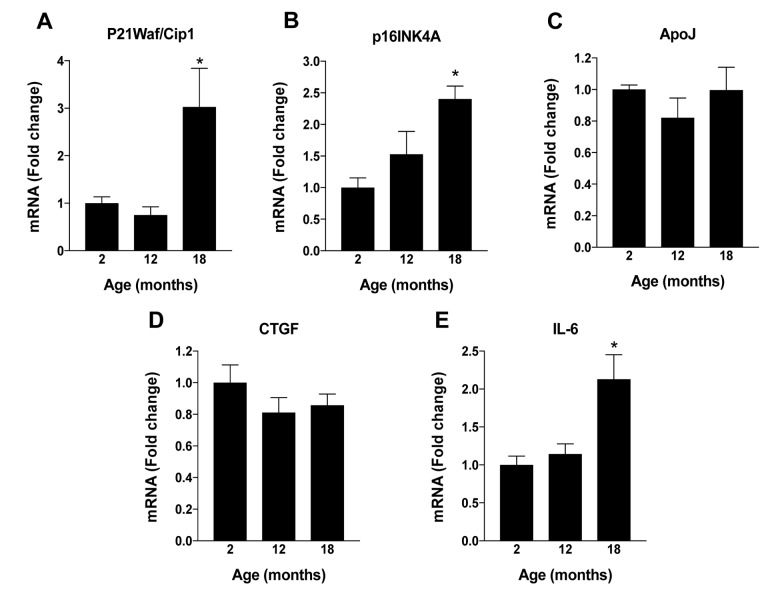

NAD+ levels decline with age in various tissues, but its status in aging RPE is uncertain. Jadeja et al. assessed NAD+ in RPE from C57BL/6J mice of different ages: young (1.5-6 months), middle-aged (7-11 months), and old (12+ months). NAD+ inversely correlated with age, remaining stable up to six months, then declining significantly, with a 40-50% reduction by 12 months (Fig. 3A). To find mechanisms behind this decline, they examined NAD+ biosynthesis enzymes: NMNAT, QPRT, and NAMPT, key to de novo and salvage pathways (Fig. 3B). NMNAT and QPRT stayed stable, but NAMPT mirrored NAD+'s decline, implicating it as crucial for NAD+ production (Fig. 3E). SIRT1, a key NAD+-dependent enzyme linked to aging, also decreased with age (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Changes in RPE NAD+ metabolism with aging in mice (Jadeja RN, Powell FL, et al., 2018).

Fig. 3. Changes in RPE NAD+ metabolism with aging in mice (Jadeja RN, Powell FL, et al., 2018).

Ask a Question

Write your own review