ONLINE INQUIRY

Rat Brain Cortex Astrocytes

Cat.No.: CSC-C8051L

Species: Rat

Source: Brain

Cell Type: Astrocyte; Glial Cell

- Specification

- Background

- Scientific Data

- Q & A

- Customer Review

The rat cerebral cortex astrocyte cell line was isolated from rat cerebral cortex tissue. Cultivated as the site of cytoplasmic neuronal activity that fills nearly every cerebral hemisphere, the cerebral cortex is a crucial organ of the central nervous system. It is responsible for various higher-brain functions, including perception, thought, language and motor coordination. Morphologically, astrocytes of the rat cerebral cortex are astral, the cytosol radiating long, branching projections that span and fill in between the cytosol and its projections to support and divide the nerve cells. These cells serve various physiological functions in the central nervous system. Not only do they build and remodel synapses, stabilize the ionic medium, regulate the blood-brain barrier's permeability, but they also nourish neurons with metabolic cargo. Furthermore, astrocytes contribute to neuroprotection, neuroinflammatory effects, and healing injuries. This cell line is commonly employed in neuroscience studies to investigate the pathological and functional functioning of the central nervous system, and is a critical vehicle in neuroscience studies to demonstrate the workings of the nervous system in healthy and diseased conditions.

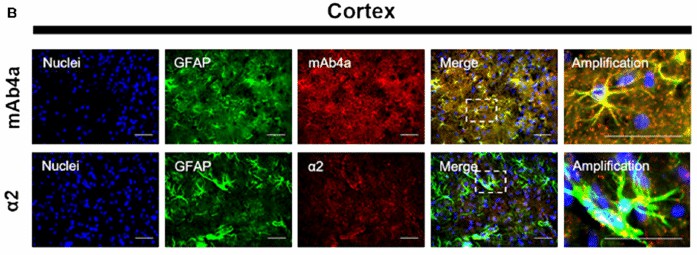

Fig. 1. Rat brain cortex astrocytes. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst, GFAP stained astrocytes are green and mAb4a/α2 immunoreactivity is red (Morais TP, Coelho D, et al., 2021).

Fig. 1. Rat brain cortex astrocytes. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst, GFAP stained astrocytes are green and mAb4a/α2 immunoreactivity is red (Morais TP, Coelho D, et al., 2021).

Long-Term Glucose Starvation Induces Inflammatory Responses and Phenotype Switch in Primary Cortical Rat Astrocytes

Astrocytes play a vital role in brain health, supporting neurons metabolically and aiding synapse formation. Overnutrition has been shown to affect astrocytes through astrogliosis. However, their response to long-term undernutrition, particularly in anorexia nervosa, is less understood. Kogel's team aims to investigate how chronic glucose shortage impacts astrocytes, using an in vitro model to mimic long-term semi-starvation of these cells.

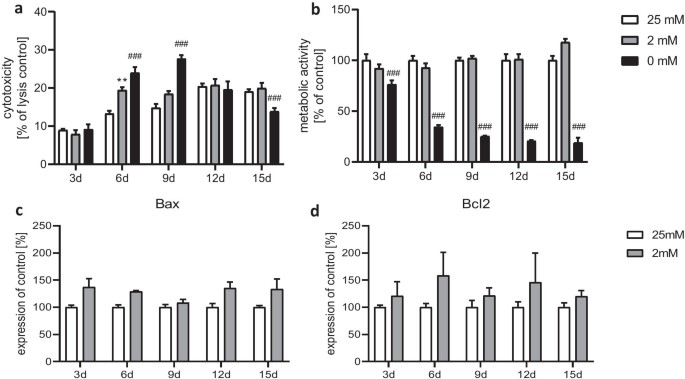

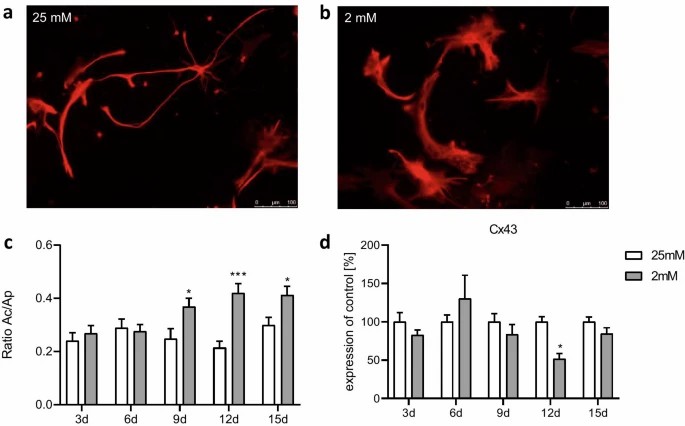

Astrocytes treated with 0 mM glucose medium showed elevated cytotoxicity on days 6 and 9 compared to 25 mM and 2 mM conditions (Fig. 2a). Metabolic activity decreased significantly from day 3 (Fig. 1b). With 2 mM glucose, increased cytotoxicity was noted only on day 6 (Fig. 1a), with no significant change in metabolic activity (Fig. 1b). Semi-starvation may induce cell vulnerability from the start, with starvation compounding the effect. This process halts after 9 days as dying cells are replaced, maintaining overall metabolic activity. Both 25 mM and 2 mM glucose showed similar effects on cytotoxicity and metabolic activity, except for cytotoxicity on day 6. Thus, these conditions were used for all further experiments. Gene expression of apoptotic markers Bax and Bcl2 slightly, but not significantly, increased in semi-starved astrocytes (Fig. 1c, d), aligning with LDH assay results. Glucose starvation influenced the morphology of primary astrocytes (Fig. 2). After 15 days in 25 mM glucose medium, most astrocytes had small cell bodies with long slender processes (Fig. 2a), characteristic of a resting state. In 2 mM glucose medium, astrocytes exhibited hypertrophic soma and processes (Fig. 2b). The ramification index, calculated as cell area (Ac) divided by projection area (Ap), significantly increased from day 9 under 2 mM glucose conditions (Fig. 2c). Connexin 43 (Cx43) gene expression, part of gap junctions, decreased from day 9 and significantly by day 12 in the 2 mM glucose medium compared to 25 mM (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 1. Effect of chronic glucose starvation on cytotoxicity (a) and metabolic activity (b) in cultured primary rat astrocytes. Measurements of the gene expression levels of the apoptotic markers Bax (c) and Bcl2 (d) showed no significant differences (Kogel V, Trinh S, et al., 2021).

Fig. 1. Effect of chronic glucose starvation on cytotoxicity (a) and metabolic activity (b) in cultured primary rat astrocytes. Measurements of the gene expression levels of the apoptotic markers Bax (c) and Bcl2 (d) showed no significant differences (Kogel V, Trinh S, et al., 2021).

Fig. 2. Effect of chronic glucose starvation on cell morphology in cultured primary rat astrocytes indicated by an immunofluorescence staining with GFAP (a–c) and a RT-qPCR of connexin 43 (d) (Kogel V, Trinh S, et al., 2021).

Fig. 2. Effect of chronic glucose starvation on cell morphology in cultured primary rat astrocytes indicated by an immunofluorescence staining with GFAP (a–c) and a RT-qPCR of connexin 43 (d) (Kogel V, Trinh S, et al., 2021).

Inhibition of Gap Junction Elevates Glutamate Uptake in Cultured Astrocytes

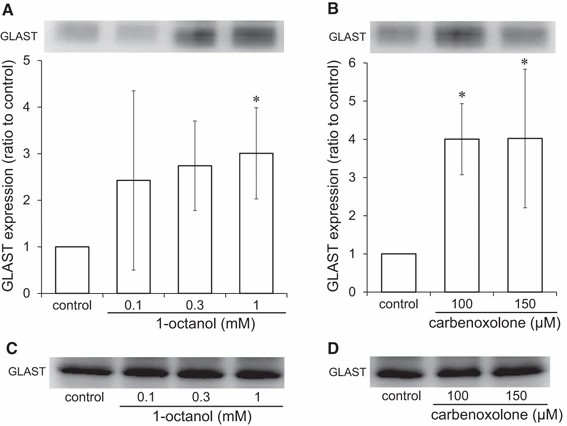

Astrocytes, vital for CNS homeostasis, clear glutamate to prevent neurotoxicity. Gap junction, anchored astrocyte networks made of connexins are involved in brain homeostasis, signaling and calcium wave production. Takano's team inhibited gap junctions in cultured rat astrocytes with 1-octanol and carbenoxolone, increasing glutamate absorption and GLAST levels on cell membranes, which suggests that inhibitors shield neurons from glutamate-induced excitotoxicity.

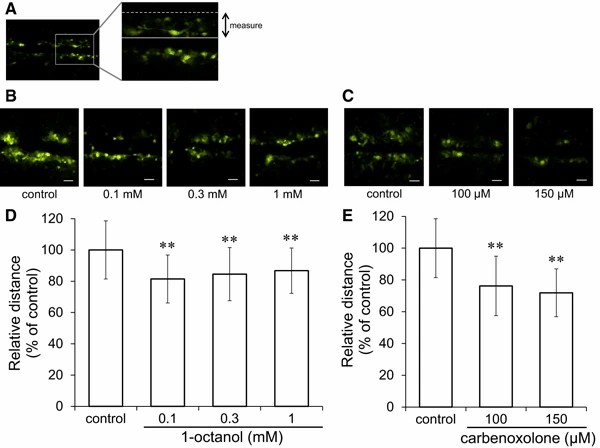

They first exposed cultured astrocytes to gap junction inhibitors 1-octanol and carbenoxolone for 20 min. The Lucifer yellow scrape-loading assay confirmed suppression of cell–cell signaling (Fig. 3a). 1-Octanol decreased dye distribution at 0.1–1 mM (Fig. 3b, d), and carbenoxolone performed well at 100, 150 M (Fig. 3c, e). In 20 min treatments, viability was not affected, whereas in 24 h treatment, viability was reduced (data not shown). Astrocytes exposed to these inhibitors uptake more glutamate. For 1-octanol, uptake increased at 0.3 and 1 mM (Fig. 4b); carbenoxolone increased uptake at 100, 150 M (Fig. 4c). They suggested examining whether inhibitors of the gap junction regulate the expression of the glutamate transporter proteins GLAST and GLT-1 on the cell surface. Cultured astrocytes were exposed to different levels of 1-octanol and carbenoxolone for 30 minutes, and protein expression was assessed by western blotting. Proteins were fractioned into "cell membrane" and "other fraction" for analysis. Both GLAST and GLT-1 were minimally detected in the "cell membrane fraction." 1-Octanol significantly increased GLAST on the cell membrane at 1 mM (Fig. 5a), while "the other fraction" remained unchanged (Fig. 5c). Similarly, Carbenoxolone also increased GLAST on the membrane without changing the "other fraction" (Fig. 5b, d).

Fig. 3. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on cell–cell communication (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Fig. 3. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on cell–cell communication (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Fig. 4. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Fig. 4. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Fig. 5. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on GLAST protein on the cell membrane of cultured astrocytes (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Fig. 5. Effects of gap junction inhibitors on GLAST protein on the cell membrane of cultured astrocytes (Takano K, Ogawa M, et al., 2018).

Ask a Question

Write your own review

- You May Also Need